Southeast England, AD 991

|

PROLOGUE

In those days raids were often made by the Danes on the English,

and they inflicted serious devastation, landing as they did in so many places by ship.

August, AD 991

It was not supposed to ever happen again: English people dying at the hands of Vikings. It had been almost forty years since the Anglo-Saxons had slain Eirik Bloodaxe, the last Viking ruler of York, and driven his warriors from England. Across the North Sea the Norsemen were said to be divided, quarreling, the Danes laying even stronger claim to Norway than to England. Yes, in the past decade or so there had been some sporadic raids along the coast – Southampton, Thanet and Chester in 980, Cornwall, Devon and Wales in 981, Dorset and the isle of Portland in 982, Watchet in Somerset in 988 – leading one monk to depict the raiders as a biblical scourge, minions of the devil. Still, compared to the old days a century past, when the Great Heathen Army had conquered half of England – the Danelaw – these were small-scale affairs, the attack on Dorset and Portland comprising just three ships. Petty theft, not conquest. This latest raid was something more. Something bigger. The first reports came from Folcanstan, modern Folkestone, where the English Channel worries away at the chalk cliffs of the Kentish coast. In Victorian times it would be a seaside resort for rich aristocrats, but at the end of the 10th century it was still just a small fishing village of a few hundred people, with the ruins of an old Roman villa on the clifftop to the north, and a 7th century Benedictine nunnery on the one to the south. The former was abandoned and empty, but the latter suitably defenseless and rich: religious artifacts and reliquaries, gold crosses, silver goblets and the like, not to mention virgin nuns to make prized slaves. Furthermore, a main road led inland, offering easy access to nearby towns and minsters. All in all, a good place to blood new men – give them a taste of battle – but tarrying too long to plunder invited counterattack. Facing an enemy army was not to Viking’s taste. They preferred to hit and run, and by the time the typical English militia of farmers and villagers, the fyrd, could be summoned, assembled, organized and led to the defense, they were long gone. But they did not go far. The next raid came just twenty-odd miles to the north, up around the convex Kentish coast at Sandwic, modern Sandwich. In those days before the River Stour silted up, the village was not two miles inland as today, but a major port right on the water. (Sandwic means “market town on the sand.”) Vikings had sacked the place in 851, and would do so again in 1006, but in the interim Sandwich had grown fat on trade, a middleman with partners both inland and across the Channel. It boasted a mint and a town wall, though of wood, the stone walls of the Roman-era fortress having long since been abandoned and fallen into ruin. The Vikings could loot the mint of silver, fill their longships with food and supplies and be gone, still ahead of any English reprisal.

A strandhögg Then north again, across the Thames estuary to East Anglia, and the richest target yet: Gippeswyc, modern Ipswich, where the River Gipping runs into the tidal, brackish River Orwell. It was one of England’s premier port towns, with a population probably exceeding four thousand, trading in pottery and wool, again with its own mint but with better defenses than Folkestone or Sandwich. The Vikings knew those defenses well, because their forefathers had built them, around a little Anglo-Saxon village at the high-tide mark, back when East Anglia was part of the Danelaw. Around the year 900 they had circled it with an earthen bulwark topped with a wooden palisade. Ipswich still had a large Danish population with little love for their Anglo-Saxon overlords, who may even have provided the raiders with a safe harbor, but the copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle written at the Old Minster in Winchester, around the time of the attack, says the Vikings eall ofereode, “overran all.” This was no minor sortie, but a full-fledged strandhogg, a marauding for plunder and slaves, just like the bad old days. Whatever business the Vikings had in Ipswich, they did not long tarry there. The fleet doubled back down to the next estuary to the south: the River Blackwater, then called the Panta, which drains the bogs of Essex – Eastseaxe, the former “kingdom of the East Saxons” – into the North Sea.

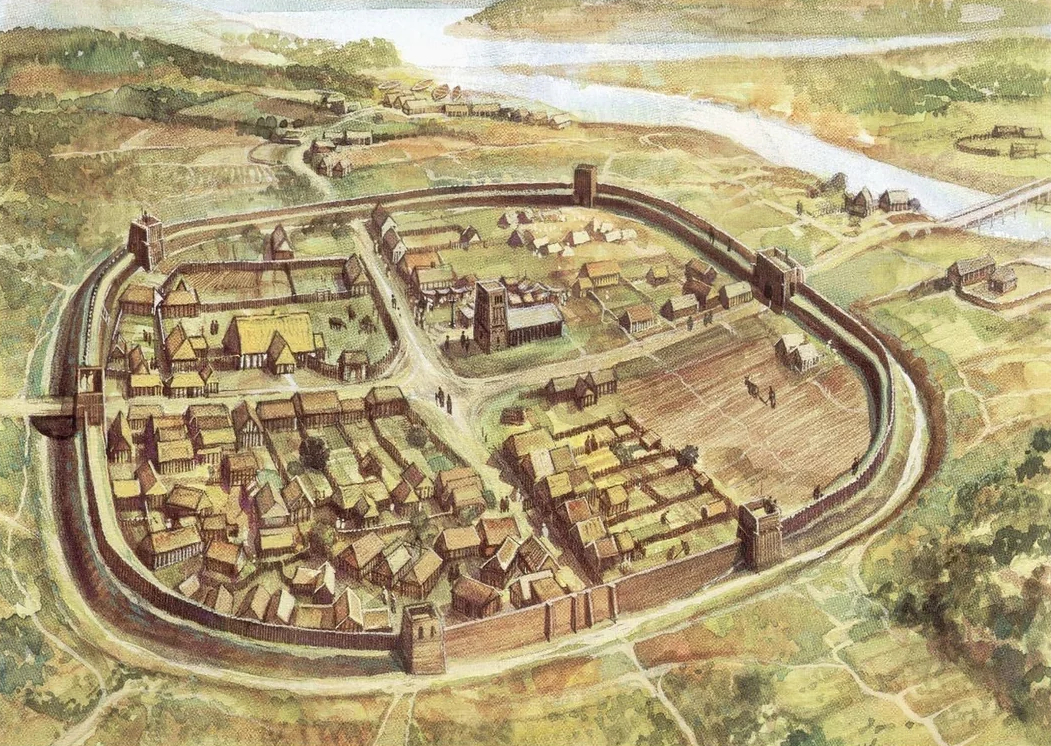

Anglo-Saxon burh On arrival the raiders had a choice. They could take the Blackwater’s northern tributary, the River Colne, to attack the county’s largest town, Colchester, or its southern tributary, the River Chelmer, to attack the second-largest, Maldon. For its part Colchester was defended by a stone wall almost twenty feet high, left over from when the town was Roman Camulodunum. Maldon, (Old English Maeldon, “Monument Hill”), atop a bluff above a bend in the Chelmer, was a burh, a town of perhaps a thousand souls, fortified in the later Anglo-Saxon fashion, with an earthen bank and wood palisade. It had proven strong enough to stand off Danish attacks in 917 and again in 924, as a result of which the town was granted a mint. That only made it, like the others, a more enticing target. The Vikings decided it was time to test Maldon’s defenses again, but probably only because of Northey Island, about a mile south of Maldon in the tidal estuary where the Blackwater lets out into the North Sea. As sea rovers, Northmen preferred islands for anchorages, which gave them maximum shorefront on which to beach their dragon ships, plus a natural moat for defense. The very first recorded Viking raid in England, in AD 793, had been at Lindisfarne, a tidal island off the Northumbrian coast. Easy pickings there had led to more and more Viking raids, and eventually to their conquest of England. The locals had to be fearing that these Vikings were in search of a base of operations from which to launch a new Danelaw, for by all accounts this, too, was a sizable Viking fleet. Returning south, however, may have been a mistake on the raiders’ part. It gave English reprisal a chance to catch up.

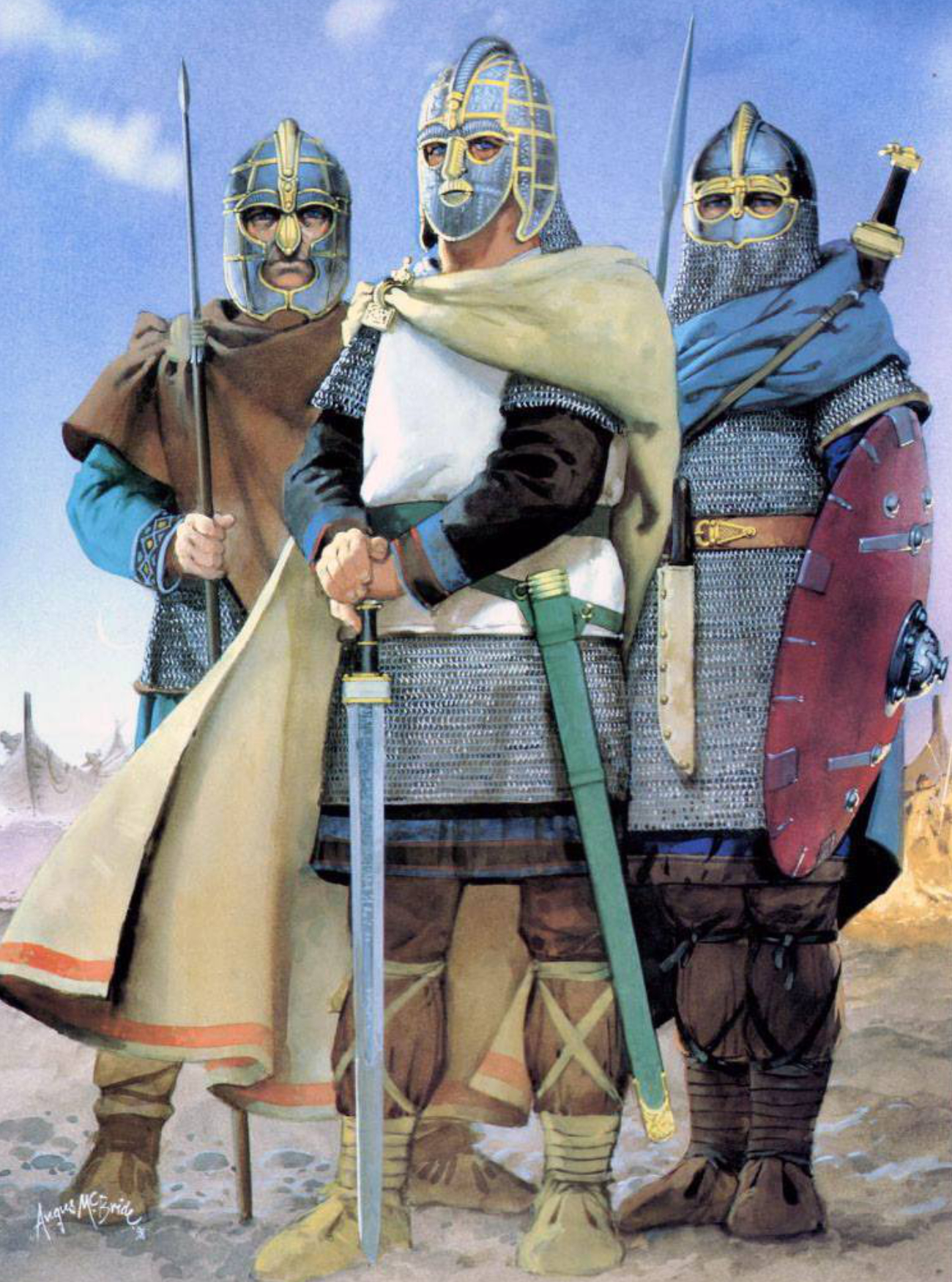

The Vikings

The Anglo-Saxons Original images by Angus McBride, courtesy of Osprey Publishing The defense of Essex fell to one Byrhtnoth, its ealdorman,* elder man, a kind of prototypical earl, second only to the king and serving as his viceroy or governor. The Liber Eliensis, the “Book of Ely,” a history compiled in the 12th century by the monks of Ely Abbey in eastern Cambridgeshire, reported, “He was articulate, big and strong, dependable in war against enemies of the kingdom, and very brave, unafraid of death.” In 991 Byrhtnoth was some sixty white-haired years old, old enough to remember the English triumph over Eirik Bloodaxe and the Danelaw, old enough even to have taken part in it, but not too old to do it again. He issued summons to the chieftains of every village in eastern Essex. Each sent his best warriors, his contribution to his lord’s fyrd. Villagers, farmers, yes, armed at best with spears, and mostly with hay forks and wood hatchets. How many there were, the old accounts do not reveal. Estimates range from a mere five hundred to three or four thousand, which in medieval times was a considerable army, certainly enough to run off a bunch of Viking raiders. On top of that the ealdorman could add another hundred or so men of his own: his hird, his personal troops, well-armed and armored, trained and fed at his expense and sworn to fight for him. “And all the shire chieftains swore loyalty to Byrhtnoth, as to a great commander,” records the Book of Ely, “because of his great integrity and faith, so that under his leadership they could best defend against the enemy.” Colchester, Byrhtnoth’s capital in Essex, is actually closer to Ipswich than to Maldon, which was a solid twenty-mile march away. A rider on a good horse might cover that in a few hours or less. Word of the Viking landing could have reached the ealdorman while the invaders were still disembarking and preparing to attack the town. Call it a day at least, though, for his summons to go out to the villages and for the fyrd to respond, then another for the English to march down through the dense forests of inland Essex, accumulating troops as they went. Byrhtnoth could only hope Maldon’s walls held off the Vikings until he came to the rescue. Imagine his shock when, arriving on the south bank of the Blackwater, he could look across the channel to Northey Island. It’s shaped roughly like a triangle pointed north, less than half a square mile in area and not quite a mile on each side. And its banks were packed with a fleet of almost a hundred beached dragon ships, and Viking warriors – three, four, five thousand or more. Far exceeding the little Viking raiding parties of the past few decades, they were on a par with the Great Heathen Army of 865, and all ready to battle Byrhtnoth and his Anglo-Saxons. He could be glad they had arrived at high tide. “Neither army could attack the other because of the high water flooding in after the ebbtide,” recorded the anonymous, contemporary English poet who would immortalize the encounter in verse. “The river separated them.”

Time lapse: The tide comes in at Maldon (Silent) Then and now, however, Northey is only an island twelve hours a day. Recent geological studies of the site suggest that over the centuries the river has carved out the southern channel, today 300 yards wide and at high tide ten feet underwater, but in 991 a little less than half that width and a little over half as deep, though with current strong enough to sweep away any army afoot. At low tide, though, Northey is a peninsula, connected by its southwest point to the south bank of the Blackwater by a narrow, Roman-era causeway that still stretches across the channel, though now of modern construction, still submerged at high tide – in effect, a bridge over the river. In a few hours the tide would go out, the water level would drop, and nothing would stop the Vikings from storming over to the mainland to kill Byrhtnoth and all his men. On October 18th 2016 high tide at Maldon was measured at 10.17 feet, still four inches short of the highest ever recorded. Meanwhile the channel, though flooded, was not so broad that one side could not taunt the other. The poet recorded that a single Viking, versed in Old English, came to the riverbank to where Byrhtnoth could see him, to shout across the water: “In the name of these bold seamen, I command you to send us treasure, and quickly, for it would be better if you paid tribute to avoid this spear-duel rather than fight hard battle with us.” That was a polite offer from the commander of a such an army. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – one of its many versions, anyway – records his name: Anlaf, the Old English version of the Norwegian Olaf. It was a common Scandinavian name, but in the year 991 there was only one such Olaf capable of putting together so large a fleet, and his name was already well known in England: Olaf son of Tryggvi. A great warrior, it was said, well-traveled, experienced in warfare, but at the same time with the manner of a king, and even said by some to be Christian. This Olaf was supposedly an exile, an outlaw in his own homeland of Norway, yet somehow he had assembled the largest Viking invasion fleet England had seen in decades. Perhaps large enough even to conquer the kingdom. Again. What exile, what outlaw could draw so many Viking warriors to his banner? Who was this Olaf Tryggvason?

“Fight! Fight! Fight!” His exploits were first recorded in verse by his skald, his court scribe, Hallfred Ottarsson, called Vandraedaskald, “Troublesome Poet.” In the late 11th or early 12th century the Icelandic priest-historians Saemund Sigfusson and Ari Thorgilsson set these oral traditions down in writing. (Both men were nicknamed frodi, “the Wise” or “the Learned,” because they were literate, a relative rarity in those days. Saemund wrote in Latin, and Ari in Old Norse.) Much of their work has been lost, but it served as source material for the Norwegian synoptics, the oldest preserved kings’ sagas: The Historia Norwegiae, “History of Norway,” by an anonymous monk probably around AD 1220, but possibly as early as 1150; the Historia de Antiquitate Regum Norwegiensium, “History of the Antiquity of the Norwegian Kings,” by Theodoricus Monachus, Theodoric the Monk, probably in the 1180s; and the Agrip af Noregskonungasogum, “Summary of the Norwegian Kings’ Sagas”, written in Old Norse by an anonymous Norwegian around 1190. That was about the time – two hundred years after Olaf Tryggvason’s death – that Odd Snorrason, a monk in the Benedictine monastery at Thingeyrar in far northwest Iceland, set down his life story. Though originally written in Latin, Odd’s Olafs saga Tryggvasonar is considered the earliest extant full-length king’s saga. Odd’s original text is lost as well, but it was expanded and translated into Old Norse by his brother monk Gunnlaug Leifsson. The 13th century Icelandic historian and politician Snorri Sturluson incorporated their work in his Heimskringla, “Circle of the World,” a collection of sagas of Swedish and Norwegian kings. And in the 14th century Olaf’s story was embellished and enlarged again as Olafs saga Tryggvasonar en mesta, “The Greatest Saga of Olaf Tryggvason,” generally believed to have been written by, or at least translated from the Latin by, the monk, abbot and scholar Berg Sokkason, with added apocryphal scenes of religious visions and miracles until the story verged on medieval fantasy. There are plenty Scandinavian chronicles that mention Olaf: among others, the Fagrskinna, “Fair Parchment”; the Orkneyinga Saga of the Orkney Islands; the Islendingabok, “Book of Icelanders,” and many more. Olaf even received passing mention in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the annals of English history. And this says nothing of the myriad praise poems and sagas sung of him by numerous Norwegian skalds. (A complete listing of the major sources may be found in the back of this book; the minor ones are too numerous to list. Olaf was that famous.) As the present volume incorporates all the versions of the sagas, it might be taken as an update to Olafs saga Tryggvasonar en mesta, but includes background and analysis not to be found in any of the medieval versions. It must be said that these many versions disagree with each other to varying extent. Most – Odd, Snorri and Berg; Theodoric Monachus; the Fagrskinna, Agrip and Historia – are Icelandic or Norwegian, which in those days was the same thing, and they generally take a flattering, not to say propagandistic, view of King Olaf. On the other hand, Saxo Grammaticus was Danish, and Adam of Bremen was German but learned Viking history at the Danish royal court, so we might consider theirs as opposing opinions. Then again, theirs are more general histories, not so focused on Olaf. The lack of detail, confusion of facts, and conflicts in the various accounts renders them impossible to reconcile. To wring a story out of it all requires a certain amount of supposition and speculation, a willingness to surmise (but always based in scholarship) in order to straighten out the timelines and fill in the blanks. On top of that, subjects the ancient writers skipped over, trusting in their audiences’ familiarity with them – the Northern European slave trade; Christianity vs. paganism; how to fight with a battle-axe – are entirely alien to modern readers, and must be enlarged upon. Finally, this story comes to us out of the mists of prehistory, when gods were said to walk the earth and magic was taken for granted. Certain scenes will strike modern readers as medieval fantasy, as well they should. We are recounting sagas here, legends, the mingling of myth and tradition, and even in the old days imagination often overtook fact. Olaf’s earliest biographers were aware of the problem. Theodoric disclaimed, “The amount of absolute truth in my present account depends entirely on those whose stories I have written down, because I have written of things not seen but heard.” And Odd Snorrason urged: I ask readers not to scoff at this story or be more skeptical or doubtful than necessary, for wise men have told us about his great deeds, if explaining little of his wondrous achievements. It often happens that lies and truth mix, and we have little to say about that, but we believe our sources will prove truthful.

On the other hand, later writers edited down Olaf’s saga. Incorporating it in his Heimskringla, Snorri Sturluson, who was not a man of religion but a politician and historian, cut a full twenty-five chapters containing the more fantastic scenes of magic and prophecy. And in the 1860s the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in his retelling of the tale in verse, edited Snorri’s 123 chapters down to twenty-two, about 7,900 lines. It may be seen that King Olaf’s saga may have lost something over the centuries. Those centuries give us moderns the advantage of cross-referencing, research and knowledge unavailable to the ancient scribes, secluded as they were in their remote monasteries and scriptoriums. We may also flatter ourselves that we’re above primitive superstition. It’s true that we don’t have to believe in magic or gods or miracles, but we should acknowledge that people once believed in all those things, and were motivated by them and acted on them. To ignore that ignores an important part of the past. What was “true” then is part of the story today. Let us recognize when fact becomes fiction, and when legend becomes history, but remember that preserving one is just as important as the other. This work, then, is more than retelling of Longfellow’s poem, or Snorri’s collection, Odd’s original saga or Berg’s embellishment. It is part compilation, part critique, part adventure, and yes, a little bit fantasy...yet all history. “But now,” wrote Odd a millennium ago, “we should hear of the great deeds of King Olaf Tryggvason.” Best just to leave the thinking until later and for now simply enjoy, as did Odd and Berg, Snorri and Longfellow, and all the scribes who have come before us, the story of King Olaf, son of Tryggvi, in the same spirit Longfellow intended when he wrote “To An Old Danish Songbook” in 1845: Once some ancient Skald, ORDER TODAY:

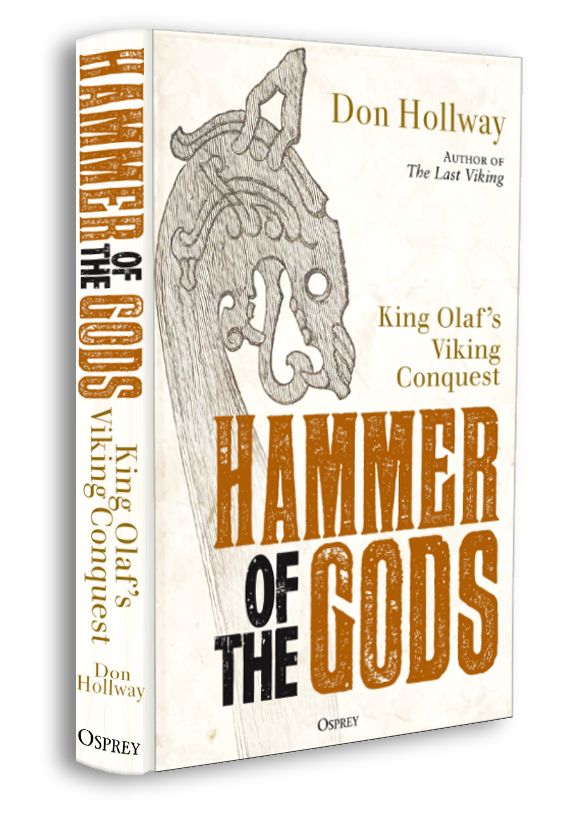

• OSPREY US • PUBLICITY CONTACTS: REPRESENTATION Scott Mendel, Managing Partner About the author

Don Hollway is an historian, illustrator, historical re-enactor and classical rapier fencer. For over 30 years his writing on history, aviation, and re-enacting has appeared in magazines ranging from Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Wild West, and World War II to Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, and Scientific American. Many of his articles are available free on his website, donhollway.com, where a number of them rank in the top two or three in global search results. He is a member of the Organization of American Historians and the Viking Society for Northern Research in the UK.

More from Don Hollway:

|